The Quiet Extinction

While much recent attention has focused on the plight of the Mallee Emu-wren, it turns out that the bird that it shares similar habitat with—the Mallee Striated Grasswren—may also be facing an extinction crisis. Sean Dooley reports on recent revelations showing that this quiet, shy bird is in danger of being forever silenced.

Overshadowed

In recent years, Australian Birdlife has brought you the saga of the desperate efforts to pull the Mallee Emu-wren back from the edge of extinction—how the South Australian population of this avian featherweight was completely wiped out in a series of devastating bushfires, and one of the largest remaining populations saved at the eleventh hour from suffering the same fate from planned burns in Victoria. We have since chronicled the tremendous efforts of BirdLife Australia and its partners to develop a conservation strategy for the emu-wren, including the successful translocation of the species back into South Australia.

All the while, another retiring bird that shared much of the same habitat as the Mallee Emu-wren was quietly heading into oblivion, yet nobody really seemed to notice. Until now.

The Mallee subspecies of the Striated Grasswren was always known to be as elusive and hard to detect as the Mallee Emu-wren, but it was thought to be in far better shape than its fragile neighbour as it had a much more extensive range, and was found in a number of large conservation reserves where it seemed to be doing quite well.

That was certainly my experience of the bird. While its elusive nature—scurrying between impenetrable clumps of triodia (spinifex) where it is almost impossible to see—meant that it took me several years to actually see one, once I had got my eye and ear in, I could reliably locate the birds at several sites by listening for their reeling, high-pitched calls throughout the 1990s. However, looking back in my notebooks, it appears that I haven’t seen a Striated Grasswren since 2002.

It seems this has been the case for many other birders. And like me, they didn’t necessarily pick up the absence of Striated Grasswrens in their notebooks. After all, the furtive nature of these shy birds meant that we were accustomed to occasionally not seeing them. It was much easier to be alarmed for the Mallee Emu-wren, because

we could see much of its known habitat go up in flames. With the Striated Grasswren it was much harder to recognise that something was amiss.

Enough people were still seeing the birds frequently enough at their regular sites that no alarm bells were raised. Even the researchers who were concerned about the downward trends of many mallee-dependant specialists didn’t single out Striated Grasswrens for specific, intensive scrutiny. There were so many other threatened species—Malleefowl, Regent Parrot, Black-eared Miner, Red-lored Whistler—ahead of them in the extinction queue demanding the researchers’ attention and limited resources.

Then suddenly, almost all the records dried up. In some instances, such as in Billiat Conservation Park in South Australia, the reason was clear—a bushfire in 2014 had engulfed the entire reserve, burning over 67,000 hectares of habitat. However, in other places that weren’t severely impacted by fires, such as the western half of BirdLife Australia’s Gluepot Reserve, where the birds were once exceedingly widespread, reported sightings fell by around 75 per cent within a decade and since 2015 the grasswrens have been recorded at only a handful of locations within the reserve. Reliable grasswren sites elsewhere such as Victoria’s Hattah-Kulkyne National Park and Yathong Nature Reserve in New South Wales seemed to suddenly dry up for sightings.

While some regular mallee visitors started to notice that they weren’t finding ‘their’ birds in the sites where they had traditionally seen them, and some research was going on in relation to this and other mallee birds in general, nobody had any inkling whether these disappearances were random local events, or whether something larger was at play across the grasswren’s entire range.

The name game

One reason why we were slow off the mark to investigate the situation was that the Mallee Striated Grasswren was considered subpopulation of a more widespread species—even if the Striated Grasswrens in the Mallee were faring poorly, there were always other populations across much of central Australia.

It is only in the last two decades that grasswren taxonomy has started to be seriously reassessed. First, the distinctive populations of what were thought to be Striated Grasswrens in the Flinders and Gawler Ranges were identified as a distinct species—the Short-tailed Grasswren—and further research using various methods, including genetic sampling, indicated that the other four main populations of Striated Grasswrens were in fact individual subspecies, and perhaps even distinct species in their own right.

Whereas the Action Plan for Australian Birds in 2010 had deemed the “sandplain” subspecies of Striated Grasswren (combining birds that inhabited sandy country in four states and territories) to have been “Near Threatened”, now that the mallee subspecies was recognised as a distinct taxon, would its conservation status be affected? With the anecdotal evidence of declines in specific locations by various birders and researchers, the signs were not good. But when BirdLife Australia’s Glenn Ehmke began the task of assessing the new subspecies’ conservation status, he needed more robust data.

Turning to Birdata, BirdLife Australia’s national bird monitoring program, started to reveal a disturbing picture. The number of records of Mallee Striated Grasswrens looked to have suffered a 75 per cent crash over the past ten years. On the face of it, something to be concerned about. However, though these records came from thousands of surveys from across the bird’s range, this of itself was not enough to be definitive. The information needed to be drilled down further to establish how robust the data was. Could there have been less survey effort in the last few years, had something changed in the behaviour of the birds that made them less easy to detect, even if they were present?

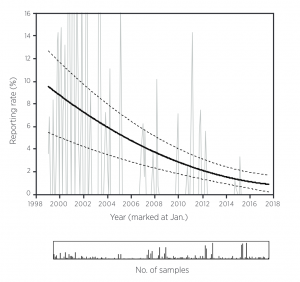

What was needed, the gold standard for data analysis, was repeat surveys over an extended period. Fortunately in the case of the Mallee Striated Grasswren, there were two such long-term projects that really helped to flesh out the general picture—the Latrobe University Mallee Fire and Biodiversity Project which monitored Victoria’s major Mallee conservation reserves. Fortunately, both projects were primarily based on the same two-hectare survey method which allowed for seamless integration of the data. Analysis of the data provided by these two projects shows a staggering decline of 88 per cent over 18 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Reporting rate trend for Mallee Striated Grasswren 1998-2018. Shown are spline (bold), 95% confidence intervals (dotted) and mean monthly reporting rate (light grey).

Applying IUCN Red List criteria to these figures, the decline was 86 per cent over three generations of the birds, which would strongly suggest that Mallee Striated Grasswrens would qualify for Critically Endangered listing. This evidence is currently under review for the forthcoming 2020 Action Plan for Australian Birds which if it comes to the same conclusions could see a rare instance of a bird going from Near Threatened to Critically Endangered in one fell swoop!

Tellingly, without the systematic monitoring data arising from the of the Latrobe and Birdata progams, Glenn would have to rely on non-systematic data (from more ad hoc observations) that gave evidence of only a maximum 53 per cent decline. Were this the only available evidence, it is doubtful that Mallee Striated Grasswren would be listed as threatened at all, let alone Critically Endangered—such is the value of systematic monitoring to give better reflect the reality of what is happening on the ground.

Probable cause

This for a bird that had already lost around 81 per cent of its historic habitat due to land clearing over the previous century and a half. That the grasswrens are disappearing from reserved land that was deemed to provide a secure home suggests something else is going on other than simply habitat loss.

We know that for many mallee woodland species—Mallee Emu-wrens in particular—the most severe recent

impacts have come from out-of-control fires that have wiped out vast tracts of prime habitat. Fires in recent decades in Ngarkat and Billiat Conservation Parks in South Australia, and the Big Desert, Wyperfeld and Bronzewing reserves in Victoria have taken an enormous toll on our mallee birds.

But there are more to the declines of the Mallee Striated Grasswren than just fires. In 2006, 8,000 hectares of Gluepot (15 per cent of the total area) was burnt; no doubt devastating for the birds in the line of the flames, but this doesn’t explain why the species has dramatically declined in areas where it was once common over the 85 per cent of the park that remained unburnt.

That the decline seemed to begin around 2003—when the Millennium Drought really began to kick in— indicates that there is something happening to the quality and productivity of the habitat across the mallee in south-eastern Australia. This is reflected in a loss of mallee woodland bird numbers in general throughout the region. BirdLife Australia’s 2015 ‘State of Australia’s Birds’, using data collected via the same method and over the same period as the data analysed for the grasswrens, revealed that the majority (22 of 39) bird species monitored were in long-term decline, with not even common species such as Yellow-plumed Honeyeater showing any sign of increase.

It seems logical to assume that the impact of drought was largely responsible, but what is most chilling is that there was little evidence of a strong ‘bounce’ in bird populations in the relatively wetter years of 2010–11. While many mallee species showed some small signs of recovery in numbers, some birds such as Black-eared Miner and the malee subspecies of Spotted Pardalote did not bounce back at all. The Mallee Striated Grasswren appears to have suffered a similar fate, showing little resilience in their ability to recover from drought.

There are some areas where the grasswrens may not be in such rapid decline, such as the Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s Scotia Reserve in far western New South Wales and perhaps in the western section of Victoria’s Murray-Sunset National Park. though more regular monitoring is needed to confirm this. Interestingly, the areas where the grasswrens may possibly be hanging on are generally in low elevation, more fertile sites, on gypsum-based soils, suggesting that they act as drought refuges. It may be that the age of the mallee post-fire could hold some relevance—there may be a window after an area has regenerated after fire that is optimal for the grasswrens—but it is an area that needs a lot more study.

With the climate showing every indication of getting hotter and drier, the future of the grasswrens, as well as many other mallee-dependant species is extremely worrying. While there may be little conservationists can do to prevent conditions worsening into the future, it is imperative that a concerted effort is put towards understanding what the current status of populations of birds like the Mallee Striated Grasswren is, and what measures we can take to increase their resilience to future conditions. Identifying and protecting drought refuges may be the key. Or it may be that, as with the translocation of the Mallee Emu-wren back to its former haunts in South Australia, there are specific conservation actions that we can take for the grasswrens. It may be that identifying and intensively protecting drought refuges could play a key role in the birds’ survival. From what we’ve seen happen at former strongholds such as Gluepot and Hattah, the situation can turn quickly for this species. We don’t have any time to lose.

The Mallee Striated Grasswren is a retiring bird; while they have moments where they appear on a dead branch out in the open and reel off a snatch of surprisingly tuneful song, they don’t reveal themselves too often. It is easy to imagine they could slip off into oblivion without anybody really noticing. We have come perilously close to this scenario. It is really only a stroke of luck that we picked up this this disturbing trend in time. But if we don’t take concerted action, and quickly, there is every chance that the Mallee Striated Grasswrens could quietly disappear completely.